Federal forces began their attempts to take Texas almost as soon as the war began; their first target being the gulf coast and the island and city of Galveston. As soon as Federal ships blockaded the port in July 1861, a back and forth wave of people off the island began. In May 1862 the Austin State Gazette reported “…all the drays and other means of transportation in the city [Galveston] have been employed under the management of Capt. M. Sellers, in removing such poor families as desire to leave the city with their effects. Many are embracing the opportunity, some leave by the cars this evening, and others will go by the cars and boats to-morrow.”1

Federal forces began their attempts to take Texas almost as soon as the war began; their first target being the gulf coast and the island and city of Galveston. As soon as Federal ships blockaded the port in July 1861, a back and forth wave of people off the island began. In May 1862 the Austin State Gazette reported “…all the drays and other means of transportation in the city [Galveston] have been employed under the management of Capt. M. Sellers, in removing such poor families as desire to leave the city with their effects. Many are embracing the opportunity, some leave by the cars this evening, and others will go by the cars and boats to-morrow.”1

Before long, however, with no bombardment from the Federals in the gulf, the Galvestonians began returning to the island, no longer able to afford paying the housing costs on the mainland. In July 1862, the Galveston Weekly News stated “… The city is gradually assuming a more cheerful appearance; ladies may be seen promenading on the side walks of an evening, more lights are visible from the houses at night, showing an increase in the population,”2 and also in a Tri-Weekly Telegraph from Houston an article of August 29th 1862 stated “The market looks lively in the morning, much like olden times. This morning there were nineteen butcher stalls, two fish do., four vegetables, and two coffee stands, all doing a good business.”3 There were enough residents in the city when a Federal warship opened fire on Confederate batteries along the shore to complete a scene reminiscent of First Bull Run with residents on the beach to watch. One spectator was killed and three were wounded.

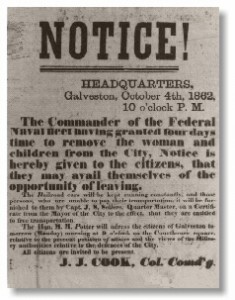

The surrender of Galveston was finally called for on October 4, 1862. This was refused and four days were given to evacuate remaining civilians. Thomas North recorded in his memoirs “The next few days witnessed a general stampede of people and valuables up country, the writer and his family with the multitude, to save them from the dangers of flying shot and shell: Every dray and available vehicle was brought into requisition to convey people and goods away from the city.”4

The surrender of Galveston was finally called for on October 4, 1862. This was refused and four days were given to evacuate remaining civilians. Thomas North recorded in his memoirs “The next few days witnessed a general stampede of people and valuables up country, the writer and his family with the multitude, to save them from the dangers of flying shot and shell: Every dray and available vehicle was brought into requisition to convey people and goods away from the city.”4

General Magruder added to the fear by issuing a proclamation which stated “Should the enemy make successful raids from the coast into the country, nothing can be expected from his forbearance….In all cases the negroes would be taken off, made to work on the fortifications of the enemy, and then armed against us….”5

The Galveston Weekly News reported that only 2000 people remained on the island; some of these were slaves. “The Yankees are said to have arrested several negroes, and put them at work at Pelican Spit, where they are fortifying and converting our batteries to their own use”6 according to the Galveston Weekly News on October 22, 1862.

Others left on the island were poor whites and the families of soldiers with neither means of leaving the island nor of support. Life on Galveston became a struggle. Citizens on the mainland collected funds, offered housing, storage, and sent food to the poor in the city. Jacob Branch, a slave at the time of the occupation remembered “So old massa took the boat and loaded it with corn and such, and we poled it down to Galveston. The people needed food so much…”7

Eventually the aid ran out and as reported by the Austin State Gazette in December 1862 “One hundred families have obtained provision from the Federals. Starvation stared them in the face. Not a particle of beef in the market. …The Relief Committee are [sic] entirely out of provisions for the poor.”8

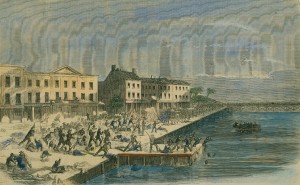

On January 1, 1863, Confederate forces succeeded in regaining control of Galveston. However, this did not mean things would be easier for the residents. Ann Raney Coleman was living in Galveston when the Federals invaded the island and during the subsequent retaking by the Confederates. Born in England in 1810, Coleman immigrated to Texas in 1832. By the time of the Civil War, Anne had been widowed twice and divorced once. In her memoirs she describes hiding during the January 1863 Battle of Galveston:

On January 1, 1863, Confederate forces succeeded in regaining control of Galveston. However, this did not mean things would be easier for the residents. Ann Raney Coleman was living in Galveston when the Federals invaded the island and during the subsequent retaking by the Confederates. Born in England in 1810, Coleman immigrated to Texas in 1832. By the time of the Civil War, Anne had been widowed twice and divorced once. In her memoirs she describes hiding during the January 1863 Battle of Galveston:

One hour was given the citizens to leave the town. I was drinking a cup of coffee when the first shell came. We had determined upon going into a ditch close by whilst the bombardment was going on. My daughter had gone and her children with her, and a great many other ladies, but I stayed behind to drink my coffee, as this was the only stimulant I took, and I was determined not to be cheated out of that…. I ran as quick [sic] as I could to the ditch, which was already full with about fifty ladies in it with their children.9

The Austin State Gazette offered this description:

The sights and sounds in the city were extremely distressing. Women in their night clothes could be seen in almost every direction, dragging their children through the streets, screaming in the extremity of their fright, and wildly seeking places of safety. To add to the hideous chorus, even the dogs all over the town set up piteous howls, as if in sympathy with their frightened mistresses. Most of the women and children soon gathered on the Gulf beach, and sheltered themselves as best they might behind the sandhills. We have heard of none of them being hurt.10

Martial law was initiated in Galveston on March 10th 1863. The addition of martial law just added to the grief and hardship of the Galvestonians. Unable to immediately return to their homes, many displaced residents would later return to find their homes in ruin or torn down for firewood. Unscrupulous soldiers were destroying crops still in the field and stealing from local farmers who had brought their produce to market. By May 1863 Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Fremantle of England described Galveston as “desolate, blockaded, and under military law. Most of the houses were empty, and bore many marks of the ill-directed fire of the Federal ships during the night of the 1st of January last.”11 Galveston would continue more or less in this state throughout the war.

Galveston was one of several communities along the coast to experience Federal attack. In August of 1862 about 250 miles down the coast from Galveston, the town of Corpus Christi was bombarded and eventually occupied by Federal forces in 1863.

Maria von Blücher described the exodus from Corpus Christi in letters to her family in Germany:

October 1862

Corpus Christi has been in a state of siege since June, with more than 700 men and soldiers in the place….Capt Kittredge came ashore with a white flag and called for surrender of the town. …Then you should have seen the migration of people!…From 1/4 of a (German) mile [1.6 km] from town and for 4-5 miles along the wayside, one saw one household after another loaded up…. They [shells] flew merrily over our house, into our field and through our fence but did not do any harm at all….A great number of houses were shot through and through; two cows were killed, and a Newfoundland dog had it head torn off by flying shrapnel. All the hens were killed except ours.12

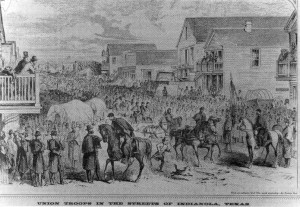

In Indianola houses were torn down to build barracks for Federal troops. General Bee evacuated and burned stored cotton and the Fort Brown garrison in Brownsville before the Federal forces arrived. The Tri-Weekly Telegraph in Houston reported the following on the activities in Port Lavaca:

In Indianola houses were torn down to build barracks for Federal troops. General Bee evacuated and burned stored cotton and the Fort Brown garrison in Brownsville before the Federal forces arrived. The Tri-Weekly Telegraph in Houston reported the following on the activities in Port Lavaca:

Lavaca, Nov. 3d, 1862

…one hour and a half was only given for the sick, women and children to leave the town. A complete stampede now took place, and the women and children, together with the sick, were placed on the cars and taken from the town….About twenty minutes or so after the time had elapsed the vessels opened upon the town a murderous fire of shell and shot, which crashed through the houses, shattering and tearing to pieces costly furniture of every description. Many women and children were still in town, it being impossible to get them all out at so short a notice, and it is a miracle that none were killed or wounded. After the fighting was over, to the surprise of the [Confederate] officers they found an ample repast prepared for them at the hotel, of which Mrs. Capt. Chesley is the proprietress. This gallant lady, assisted by her accomplished daughters, and the noble Mrs. Dunn, remained a part of the time under a galling fire, and cared for the wants of the tired soldier. Thus, when the town was entirely deserted by the citizens, did these noble ladies have in view the comforts of those who were battling for the rights of society, and the defence of their homes and firesides. Can our country be conquered when we have such mothers and such daughters?—Never!13

These invasions, however, were only along the coast of Texas. The inland did not see the bombardments and occupations of the Federal troops. Instead, the interior had its own invasion.

1 Austin State Gazette. May 31, 1862, page 1, column 2

2 Galveston Weekly News. September 1, 1862, page 2, column 5

3 Tri-Weekly Telegraph. September 1, 1862, page 2, column 5

4 North, Thomas. Five years in Texas: or, What you did not hear during the war from January 1861 to January 1866. A narrative of his travels, experiences and observations, in Texas and Mexico. Elm Street Printing Co., Cincinnati 1871, page 106

5 Austin State Gazette. December 31, 1862, page 2, column 2

6 Galveston Weekly News. October 22, 1862, page 1 column 1

7 Tyler, Ron and Lawrence R Murphy, eds. The Slave Narratives of Texas. State House Press, Austin, 1997, page 100.

8 Austin State Gazette. December 31, 1862, page 1 column 2

9 King, Richard C., ed. Victorian Lady on the Texas Frontier: The Journal of Ann Raney Coleman. University of Oklahoma Press, 1986, page 158.

10 Austin State Gazette. November 23, 1861, page 1 column 3.

11 Fremantel, Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Three Months in the Southern States: April – June 1863. University of Nebraska Press, 1991, page 71.

12 Cheeseman, Bruce S. ed. Maria von Blucher’s Corpus Christi. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2002, page 130-132

13 Tri-Weekly Telegraph. November 10, 1862, page 2 column 3.