Some historians believe that as many as one-third of Texas’ population remained neutral after secession and that another third supported the Union.1 Others such as George Bernard Erath, an Austrian immigrant to Texas in 1833 and former Republic of Texas congressman, decided to support the Confederacy, regardless of his feelings and beliefs—“I believed in our right to secede, but was not in favor of making use of the right. When the people decided by vote to do so I went with the majority of my State.”2

Still others simply left or were forced to leave the state as reported in the Austin State Gazette “We learn from Capt. Harrison that the men in Northern Texas who have been opposing the action of Texas in favor of the South, and who have had secret complicity with the Black Republicans, are now leaving the State. Some one hundred and twenty wagons were seen wending their way to the North.”3 Some of these men later joined the Union army; it is estimated that 2,000 Texans did so.4

Groups such as the Peace Party or the Loyal League were organized to actively undermine the Confederacy in Texas through spying, resisting the draft, and deserting from the Confederate army during battle. The San Antonio area had a large share of Union sympathizers who celebrated Confederate defeats and attempted to discredit the Confederate economy by overcharging when Confederate money was used for purchases. Pro-Union Germans in the city published broadsides calling for a Unionist revolt, the death of civic leaders, and the hanging and burning of secessionists.

Terrorism and violence occurred on both sides, resulting in destruction of property and numerous deaths.Organizations such as the Knights of the Golden Circle took actions against individuals and businesses that openly supported the Union. These groups took credit for several retaliatory actions against Union sympathizers such as destroying newspaper offices that printed pro-Union articles. Treason charges were trumped up against Unionists who had “something to say on all passing events” or because of their ability to “create discontent and dissatisfaction” or for being “active in speaking his mind…”5 Unionists from the Hill Country began physically attacking secessionists and killed a Confederate spy.

Unionists, however, were the minority in 1860s Texas and suffered the most violence. The daughter of German immigrants, Mathilda Doebbler Gruen Wanger was born in 1856 in Fredericksburg, in the hill country of Texas. Though young at the time of the war, she relates in her memoirs “how the people who sympathized with the North during the Civil War had to hide out and sleep in the bushes at night to prevent being killed…. A band of men, mostly hard, bad characters, called guerillas, murdered many people.”6

Some Unionists attempted to enter Mexico and join the Union army there. This was not always the safest thing to do. While camped on the Nueces River in August of 1862, a group of Unionists on their way to Mexico were attacked by mounted Confederate soldiers. Nineteen Unionists were killed, and nine were wounded. The nine wounded were executed a few hours later. Eight survivors were later killed by Confederates in October 1862 while trying to cross into Mexico, eleven reached home, and others escaped temporarily to Mexico or to California.7

After the war the remains of the Unionists killed at the battle site were gathered and interred at Comfort, Texas where a monument commemorates the Germans and one Hispanic killed in the battle and subsequent actions.

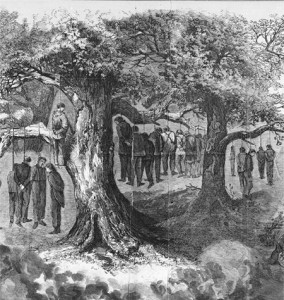

Even the suspicion of being pro-Union or an abolitionist could be dangerous in Texas. Fired by rumor and fear, the Great Hanging at Gainesville in October 1862 is an example.

In September, the state troops were activated in North Texas with orders to arrest all able-bodied men not reporting for military duty. Northern Texas was settled in a large part by people from the Upper South and the Midwest who had voted against secession. Many of the men in this area joined the Union League as a way to resist military duty in the southern army and provide defense along the northern frontier. It was believed by some, however, that the Union League planned to storm the arsenals in Gainesville and Sherman.

On October 1, more than 150 men were arrested and charged with insurrection or treason. A “citizen’s court” of twelve jurors was assembled. Seven of the accused were convicted; however, a vigilante mob hanged fourteen before the jurors had recessed. Two more were killed by unknown parties the following week.

On October 1, more than 150 men were arrested and charged with insurrection or treason. A “citizen’s court” of twelve jurors was assembled. Seven of the accused were convicted; however, a vigilante mob hanged fourteen before the jurors had recessed. Two more were killed by unknown parties the following week.

A decision was made to release the remaining prisoners, but this was reversed and many of the prisoners were tried again. Nineteen more men were convicted during the second trials and hanged. Ten other men were executed in Sherman and in Decatur and a prisoner was shot in Denton.

Surviving members of the Union League fled with the prisoners’ families, leaving many of the bodies of the executed unclaimed, which were buried in a mass grave. All totaled 68 men were brought to trial. Thirty-nine of them were found guilty of conspiracy and insurrection, sentenced and immediately hanged. Three other prisoners who were members of military units were allowed trial by Court Martial at their request and were subsequently hanged by its order. Two others broke from their guard and were shot and killed.

It wasn’t necessarily politics that kept some men from joining the army. Even before the vote on secession and after their initial wave of enthusiasm, men were having second thoughts. Gideon Lincecum wrote in February 1861 of some of the Minute Men in his area making “private applications, to withdraw their names.”8 Volunteers were becoming scarce in 1862 and in December of 1863 Mary Adams Maverick from San Antonio wrote to her son. “It would astonish you to see how many able-looking men congregate on our street & none of them going, only talk-talk-& very few work on the fortifications.”9

With the passing of the Conscription Act of April 1862 some proclaimed pro-southern Texas men went into hiding to avoid being conscripted or arrested as deserters. Abram Sells, a former slave born on a plantation southwest of Newton, Texas was interviewed by the WPA in Jamestown, Texas. In his interview he remembered “how some of them [men] marched off in their uniforms, looking so grand, and how some of them hid out in the wood to keep from looking so grand”10 Edmund Smith wrote in1864. “The frontier counties…are…a grand city of refuge where thousands of able-bodied men have flocked to escape service in the confederate Army.”11 Brig. Gen. Henry McCulloch recognized this problem in 1863 “I have received most pressing letters already from different portions of the District [Northern Sub-District of Texas], urging me to take steps to arrest Deserters and conscripts that have gone into the brush in large numbers in some portions of the District. These men live off of the property and produce of the people near their camps and are a terror to the country about them, and in many instances the lives of our best friends are in danger from them.”12

This support from the community was not always as involuntary as the quote makes it sound. Family members living near hiding places often placed food, clothes, and money in places where the hiding men could find them. Annie Hawkings told a WPA interviewer “My job every day was to take a big tray of food and sit it on a stump about a quarter of a mile from our house. I done this twice a day and ever time I went back the dishes would be empty. I never did see nobody and didn’t nobody tell me why I was to take the food up there but of course it was either for soldiers that was scouting ’round or it may been for some lowdown dirty bushwhacker, and again it might a been for some of old Master’s folks scouting ’round to keep out of the army.”13

Unfortunately, some resistance resulted in death. The Tri-Weekly Telegraph published the following in December 1862: “We regret to learn resistance is being made to the conscript act, in the county of Angelina. The number engaged n this resistance is said to be about twenty. They fired upon the enrolling officer in his carriage a few days ago, but happened not to hit him. At our latest advices they were still in rebellion to the law, and were giving protection to some deserters from the army, who had been secreting themselves in the Angelina swamps for some months.”14 The enrolling officer in Comanche County was not so lucky; he was “shot full of holes” in 1863 according to the Galveston Weekly.15

Texas women joined the fight against the conscription of their men. In one instance after the militia was mobilized for draft purposes, women stormed a school house in Industry, Texas, were the militia were gathered. The women took after the captain, whipping and clubbing him. When they went after the next-in-command, he drew his six-shooter and threatened to shoot the first person that assaulted him. To combat the desertion problem Gen. Magruder issued an order, that any lady who will arrest or cause to be arrested a deserter, would be entitled to a furlough for twenty days for any one in the army–whether husband, brother or lover.16

1 Elliott, Claude.”Union Sentiment in Texas 1861-1865″, Volume 50, Number 4, Southwestern Historical Quarterly Online, http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/publications/journals/shq/online/v050/n4-contrib_DIVL7560_print.htm [Accessed Mon Nov 19 20:18:14 CST 2007]

2 Erath, Lucy A., “Memoirs of George Bernard Erath,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly Online, Volume 27, Page 156, July 1923, http://www.tshaonline.org/shqonline/apager.php?vol=027&pag=142 [Accessed11-28-2009]

3 Austin State Gazette, May 4, 1861, page 3 column 1

4 Texas Military Forces Historical Sketch “Civil War” www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/tnghist10.htm

5 Barr, Alwyn. Records of the Confederate Military Commission in San Antonio, July 2 – October 10, 1862″, Southwest Historical Quarterly Online, Volume 71, Pages 257-258, 262, and 275 (October 1867),

http://www.tshaonline.org/shqonline/apager.php?vol=071&pag=277[Accessed 08-20-2009]

6 Exley, Jo Ella Powell, ed. Texas Tears, Texas Sunshine. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 1985, page 111. Two such event are known as the “Great Hanging at Gainesville” and the “Battle of the Nueces.” See the Texas HandbookOnline (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/index.html) for additional information.

7 Known as the Battle of the Nueces

8 Lincecum, Jerry Bryan. Gideon Lincecum’s Sward. University of North Texas Press, 2001, page 102

9 Marks, Paula Mitchell. When Will the Weary War Be Over? The Civil War Letters of the Maverick Family of San Antonio, Book Club of Texas, 2008, page 91.

10 Tyler, Ron and Lawrence R. Murphy, eds. The Slave Narrative of Texas. State House Press, Austin, 1997, page 112

11 Pickering, Davis and Judy Falls. Brush Men and Vigilantes: Civil War Dissent in Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2000, page 21.

12 Ibid

13 Baker, Lindsay and Julie P Baker. Till Freedom Cried Out: Memories of Texas Slave Life. Texas A&M University Press, College Station 1997, page 32.

14 Tri-Weekly Telegraph. December 24, 1862, page 1 column2.

15 Galveston Weekly News. July 1, 1863, page 2 column 6

16 Austin State Gazette. April 6, 1864, page 2, column 1