|

By 1864 Texans began to sour on the war. The severe shortages

and inflation experienced earlier by the other southern states had caught up with Texas. Paper could not be had, fabric was

even more scarce, medicine was not available, and even seed to plant crops could not be found in some parts of the state.

Rebecca Adams of Fairfield, Texas wrote “The children's next aprons and dresses must come out of the loom. I have

enough calico to make them all one dress a piece that must be saved for Sunday wear.”1 Elizabeth Neblett reported

in 1864 “I learn it [confederate money] fell in a few days in Houston to 30 for one & since 50 for one & that

most of the stores are closed.”2

Ralph Smith described the army in Galveston fighting off Galveston

residents demanding food “…Our nearest approach to battle was with our own men when we were called out one night

to protect Col. Hawes quarters from the assault of a mob, composed of resident soldiers and their families. These soldiers

demanded that the government issue rations to their starving wives and children, which being refused on account of the depleted

condition of our commissaries, had come in a riotous mob to secure provision by force if persuasion did not avail."3

Rioting also occurred in Houston as soldiers

broke into government buildings and warehouses to obtain supplies. Rioting spread to other towns, including Austin, San Antonio,

Gonzales, La Grange, and Henderson.

Even with the shortages, however, “Strangers from the east

who visit here tell us we know nothing of the war.”4 wrote Mary Maverick.

Seemingly to agree with them she wrote in 1864, San Antonio is “…always crowded, the stores full of goods &

plenty of melon & peaches for sale on the plaza. The place is actually flourishing & silver abounds.”5

But Kate Stone lamented “Only the

necessaries, none of the luxuries of life.” in east Texas.6

Parties continued, in fact seemed to increase as the war wore on. Younger family

members went to parties and dances “frequently” regardless of their worn wardrobes. One such party is described

by Elizabeth Neblett “There was a big party (one of these party's that are all the fashion now)…The house

was full at Alston's, had two fiddles, and dancing, and a nice supper…”.7

By 1865 the Federals had abandoned Brownsville allowing for regular

trade to be reestablished across the Mexican border from the city, causing prices to fall dramatically and goods to be more

plentiful. Amzi Wood, a commercial agent in Matamoros reported “…I found about 125 vessels at anchor off the

mouth of the Rio Grande and hardly an American sail among them. There is a great deal of cotton being shipped from this port

all of which is claimed to belong to the Mexicans. There is also a large amount of merchandise shipped to this place to the

extent that the whole thing is a drug upon the market here."8

Blockade running at Galveston also increased toward the end of

the war; at least 37 vessels were active in running the blockade in the last six months of the war. One reason for this increase

in successful runs can be attributed in part to the Federals relaxing the pressure on the trade through Texas; the Confederacy

was on its last leg east of the Mississippi and the Trans-Mississippi didn’t seem so important.

Troops in Texas soon

began deserting and returning to their homes, plundering civilians’ pantries and public stores along the way. At Marshall

Confederate commanders issued orders "to place strict guards around their respective commands…and adopt such other

measures" as needed to keep their men in camp to prevent "further molestations of the citizens."9

Soldiers’ homes were established in a number of counties

in eastern and central Texas to accommodate and feed the returning troops. The homes were supported through donation and volunteers

and sometimes by the county. Some of the homes were established in public buildings and served as a central location for the

county. Others were in private homes and operated as way stations throughout the county, such as in Freestone County.

Galveston Weekly

News, February 1865

Fairfield,

January 21st, 1865.

Ed. News:--

…The keepers of these homes are required

to register their houses as such at the Clerk's office, keep proper registers, examine passes, papers, &c., of each

visitor, present his register with his account quarterly to the County Court for payment, which accounts are audited and paid

by the County Treasurer. No soldier is allowed to remain longer than one night at any one of these homes

unless sick or disabled. No drunkenness or gambling is allowed.

…I have not

heard of any County having more than seventy-five soldiers' homes, but believe each ought to have at least that number.

I

am, most respectfully, your obd't serv't,

J. C. Yarbro, C. J.10

|

| Palmito Ranch 2009. Photo by William McWhorter |

The last battle of the war was fought May 13, 1865 at Palmito

Ranch near Brownsville, Texas, a month after Appomattox. At the same time, the Confederate governors of Arkansas, Louisiana,

Missouri, and Texas were authorizing Kirby Smith to disband his armies and end the war. General Kirby Smith formally surrendered

at Galveston on June 2.

|

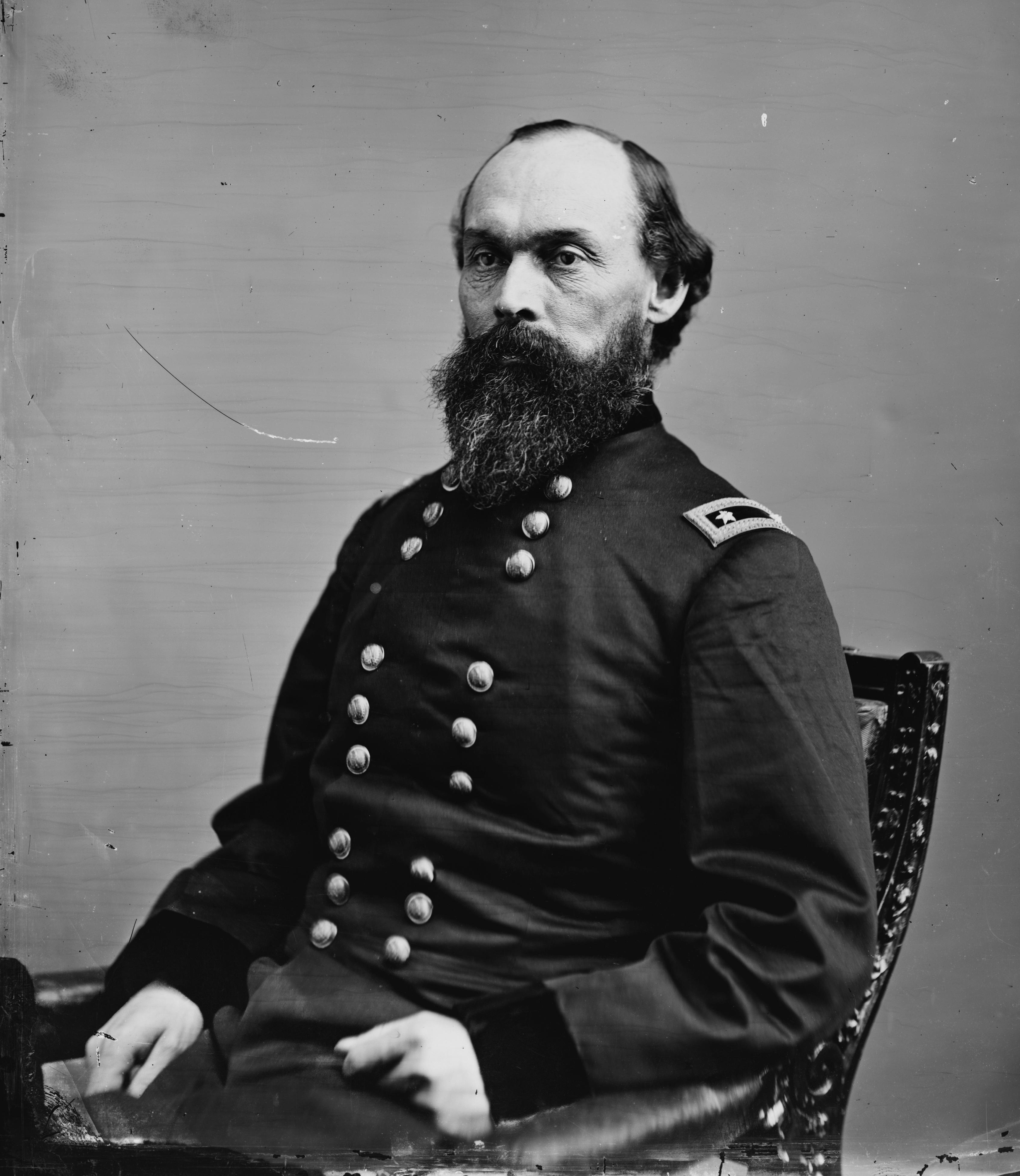

| Gordon Granger |

Just over two weeks later on June 19, 1865, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger

arrived at Galveston and immediately issued orders declaring that the Emancipation Proclamation was in effect and that all

slaves in Texas were free; this is now celebrated as the Texas state holiday of Juneteenth.

Former slave Lewis Jenkins

remembered the day: “One day whilst we was eating our dinner, our Master said, ‘all you, young and old, when you

git through come out on the gallery, I got something to tell you.’…’This is military law, but I am forced

to tell you.’ He says, ‘this law says free the nigger, so now you is jest as free as me by this law. I can't

make you all stay wid me 'less you want to, therefore you can go any place you want to.’ That was about laying-by

crop time in June. It was in June 19th…”.11 Phyllis Petite of Rusk County didn’t know how to react to the news “We

just stand and look and don't know what to say about it.”12 Others left immediately

“When the War was over you'd see men, women and chillun walk out of their cabins with a bundle under their arm.

All going by in droves, just going nowhere in particular” remembered Lou Smith.13

For some slaves in Texas it would be several days or even months

before they knew they were free. Alice Rawlings in Cass County wasn’t told about her freedom until the six months later,

after all the crops were in. John White wasn’t told at all by his master; he learned about it from a soldier who stopped

by the plantation on which he worked.

|

|

1 Exley, Jo Ella Powell, ed. Texas Tears and Texas Sunshine. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 1985, page 140 2 Murr, Erika L. A Rebel Wife in Texas:

The Diary and Letters of Elizabeth Neblett 1852-1864. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2001, page 359 3 Gallaway, B. P. Texas,

the Dark Corner of the Confederacy: Contemporary Accounts of the Lone Star State in the Civil War. University of Nebraska

Press, 1994, page 191 4 Marks, Paula

Mitchell. When Will the Weary War Be Over? The Civil War Letters of the Maverick Family of

San Antonio. Book Club of Texas, 2008, page 165 5

Ibid, page 166 6 Anderson, John

Q. Brokenburn: The Journal of Kate Stone 1861-1868. Louisiana State University Press,

1955, page 275 7 Murr, page 339 8 Amberson, Mary Margaret McAllen, James McAllen & Margaret

McAllen. I Would Rather Sleep in Texas: A History of the Lower Rio Grande Valley & the

People of the Santa Anita Land Grant. Texas State Historical Association, Austin, 2003, page 254 9 Henson,

Margaret Swett & Deolece Parmelee. The Cartwrights of San Augustine: Three Generations

of Agrarian Entrepreneurs in Nineteenth-Century Texas. Texas State Historical Association, Austin, 1993, page 239 10 Galveston Weekly News. February 1, 1865, page 1 column 6 11 Baker, T. Lindsay

& Julie P, ed. Till Freedom Cried Out: Memories of Texas Slave Life. Texas A&M

University Press, College Station 1997, page 41 12 Ibid, page 76 13 Ibid, page 97

|