|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Juan Nepomuceno Cortina Goseacochea |

At the

same time John Brown was raiding Harper’s Ferry, Juan Cortina, the son of an aristocratic Mexican family began raids

along the Mexican-US border in an attempt to protect the rights of Mexicans who lived in that region. When Cortina witnessed,

Brownsville city marshal, Robert Shears, brutally arrest a Mexican who had once been employed by Cortina, he shot the marshal

and escaped with the prisoner. Later that year, he rode into Brownsville again and seized control of the town. He killed five

men during this second raid.

Native American raids on Anglo farmsteads were also increasing at this time. Between October

1857 and April 1858, it was claimed that 500 to 800 horses were stolen and some twenty-five settlers were killed by Indian

attacks.1 Texans felt that they could do a better job of protecting the frontier than the Federal government.

Then in the summer of 1860 north Texas experienced fires that destroyed large portions of several towns including Dallas.

The cause of the fires was assumed to be arson and the newspapers placed the blame on abolitionists and slaves. It was later

determined that the fires were started by unstable phosphorous matches improperly stored during the summer heat wave. However, the perceived lack of protection on the frontier, along

with the fear of presumed abolitionist terrorism, set Texas on the road toward secession.

With the election of Lincoln, everyone seemed to be in support of leaving the Union. A stanch Confederate and prolific

letter writer, Gideon Lincecum (1793-1874) was a physician, philosopher, and naturalist who arrived in Texas 1848. He noted

in a letter on December 3, 1860 “Mass meetings, conventions, and minute men is all the go. Lone Star flags and blue

cockades are fluttering to every breeze and glittering on every hat, as well as on the breast of many of our patriotic ladies.”2

|

| Baylor Female College, Independance, TX |

The Lone Star flag became the symbol of Texas’s secession; even the female students at Baylor University in Independence

got in the act in December 1860, and “…with their own hands hoisted the Lone Star from the cupola of the University

building."3

Sam Houston, Governor of Texas, refused to call a special session

of the legislature to consider secession saying "To secede from the Union and set up another government would cause war.

If you go to war with the United States, you will never conquer her, as she has the money and the men. If she does not whip

you by guns, powder, and steel, she will starve you...".4

In January

1861, an unofficial secession convention was convened, which prompted Houston to call the legislature to session in an attempt

to declare the convention illegal. This backfired when the legislature validated the convention instead. The house chambers

on the second floor of the capitol were turned over to the convention. Sam Houston continued to work from his first floor

office and referred to the convention delegates as “the mob upstairs.”

|

|

|

|

| Samuel Maverick |

|

| Mary Maverick and Children |

Samuel Maverick of San Antonio was one of the legislators called

to Austin by Sam Houston. The Mavericks are a well known name in Texas; one of Texas' first families. Samuel had been

at the Alamo just prior to the siege and served as a delegate to the 1836 Independence Convention. Maverick brought his wife

Mary and their new son Samuel Jr. to Texas in 1838 and settled in San Antonio. On January 24 1861 Samuel Maverick wrote to

his wife from Austin "We passed unanimously a resolution denying the right to coerce a seceding state. We are passing

a bill ordering a further election in counting that have not voted for the convention [sic]--thus recognizing the convention

and further, that the action of the convention be submitted to a direct vote of the people...5

In the Ordinance of Secession Texas laid out her reasons for leaving the United States, basically those issues that began in 1859: the lack of protection

by the Federal government on the borders and the frontier and the abolition of slavery. The convention’s vote on the

ordinance occurred February 1, 1861 with a vote of 166 for to 8 against.6 The secession question was put to the

general public as a referendum on February 23.

However,

before the public elections could take place, the Committee on Public Safety seized all federal property in Texas and ordered

the evacuation of federal troops in the state. In addition the secession convention sent delegates to Montgomery, Alabama

to help establish the Confederate States of America, one might suppose in anticipation of a favorable secession vote.

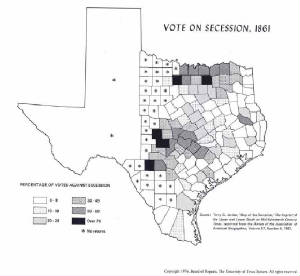

Which did happen. But it was far from unanimous; 18 counties cast a majority against secession and 11 others cast as

much as 40 percent against.7 The majority of the anti-secession votes were from counties with large German populations

and counties in north Texas, which was settled extensively by emigrants from the north and included populations with few slaveholders.

The Secession

Convention reconvened on March 2, Texas Independence Day. The Ordinance became effective on March 5, the same day Texas was

accepted into the Confederate States of America.

|

| Amelia Huddleston Barr |

All state officers were asked to take an oath of loyalty to the CSA. Amelia Barr went to the capitol to watch as the

officers gathered at the capitol building. Barr was born in England in 1831, immigrated to America and eventually settled

in Austin, Texas in 1856 where her husband became an auditor for the state. Barr describes the following as Lieutenant Governor

Edward Clarke approached to take the CSA loyalty oath, “he reached the desk, on which the Ordinance of Secession lay,

my Unionist friend, a bright, clever girl, of about sixteen years old, leaned forward and spit directly on the centre of it.

There was a little soft laughter from the women sympathizers…"8

Sam Houston

refused to take the oath saying "In the name of the constitution of Texas, which has been trampled upon, I refuse to

take this oath. I love Texas too well to bring civil strife and bloodshed upon her."9 Houston was summarily

removed from office and his Lieutenant Governor Edward Clark became Texas’ first Confederate governor.

|

| Maria Augusta von Blucher |

It appears that many in Texas assumed that

the state would revert back to being a Republic upon seceding from the US. Maria Augusta von Blücher, an 1849 immigrant

from Berlin, Germany living in Corpus Christi described this sentiment in a letter to her mother on February 19, 1861 “Texas,

too, has now seceded from the United States, and people's opinions about the future of the southern states differ widely.

Some think that they would form a more effective republic on their own and would establish direct commerce and traffic with

Europe. Others fear war with Mexico, Indians, and excessive taxes. So far everything is as before."10

|

|

|

1

Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Indian Relations" http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/II/bzi1html

(accessed October 13, 2009)

2 Lincecum, Jerry Bryan. Gideon Lincecum's Sword.

University of North Texas Press, 2001, page 72

3 "Hurrah for the Girls". Austin

State Gazette, December 29, 1860, page 1, column 8

4 Sam Houston Memorial Museum http://www.shsu.edu/~smm_www/History/quotes.shtml

5 Marks, Paula

Mitchell. When Will the Weary War Be Over?

The Civil War Letters of the Maverick Family of San Antontio, Book Club of Texas, 2008, page 27.

6 Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Secession Convention," http:''www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/SS/mjs1.html

(accessed September 2, 2009)

7 Ibid

8 Barr, Amelia E. All

the Days of My Life: An Autobiography. D. Appleton and Company, 1913, page 226-227

9 Sam Houston Memorial Museum http://www.shsu.edu/~smm_www/History/quotes.shtm

10

Cheeseman, Bruce S ed. Maria von Blucher's Corpus Christi. Texas A&M University

Press, College Station, 2002, page 128

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|